Important: Before considering any investments, please ensure you understand what to expect.

Summary

A while ago, I stumbled upon a TUI analysis claiming the company was worth €10 billion, while its market cap sat at just €3 billion. It took me five minutes to understand the core hypothesis—and over a month to figure out whether it holds up.

A few months later, I can say with 100% conviction that… I’m not sure. But I’m confident that TUI is worth at least €6 billion, probably more.

If I’m right, I’ll double my money. If I’m wrong, I’ll probably lose no more than 30%. With those odds, I feel comfortable committing a significant portion of my portfolio to TUI—and I did.

I’ve invested €77,000 in TUI so far, acquiring shares at various points from November 2024 to April 2025, at an average cost of €6.69 per share. It’s my largest investment, and I’m considering adding even more.

This analysis explains my reasoning.

About TUI

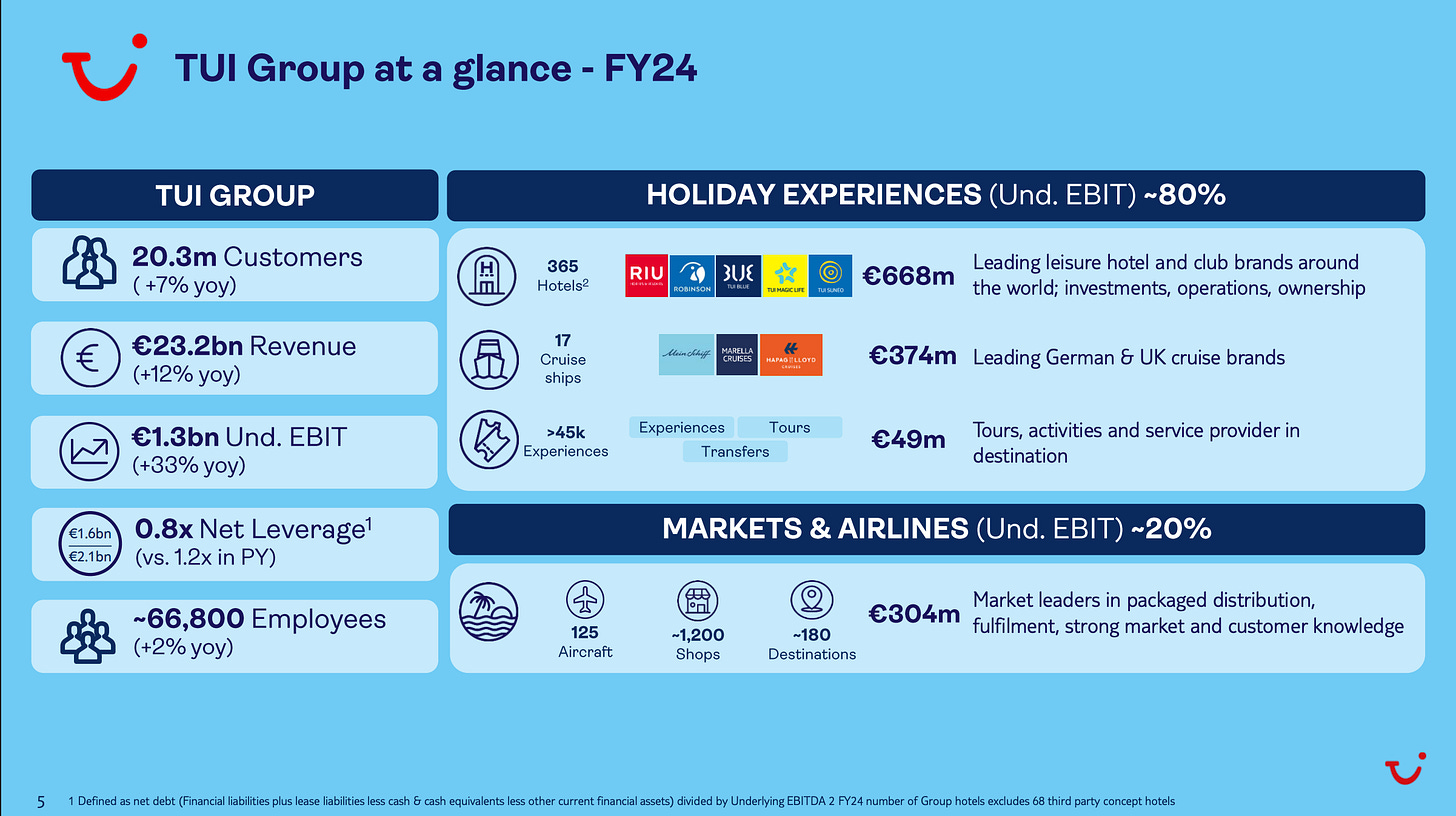

TUI AG (trading as TUI Group) is a German multinational leisure, travel and tourism company; it is the largest such company in the world. TUI is an acronym for Touristik Union International ("Tourism Union International"). TUI AG was known as Preussag AG until 1997 when the company changed its activities from mining to tourism. It is headquartered in Hanover, Germany, and trading on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and Hanover Stock Exchange.

It fully or partially owns several travel agencies, hotel chains, cruise lines and retail shops as well as five European airlines.

- Source: Wikipedia (TUI Group)

Value Investors Club Analysis

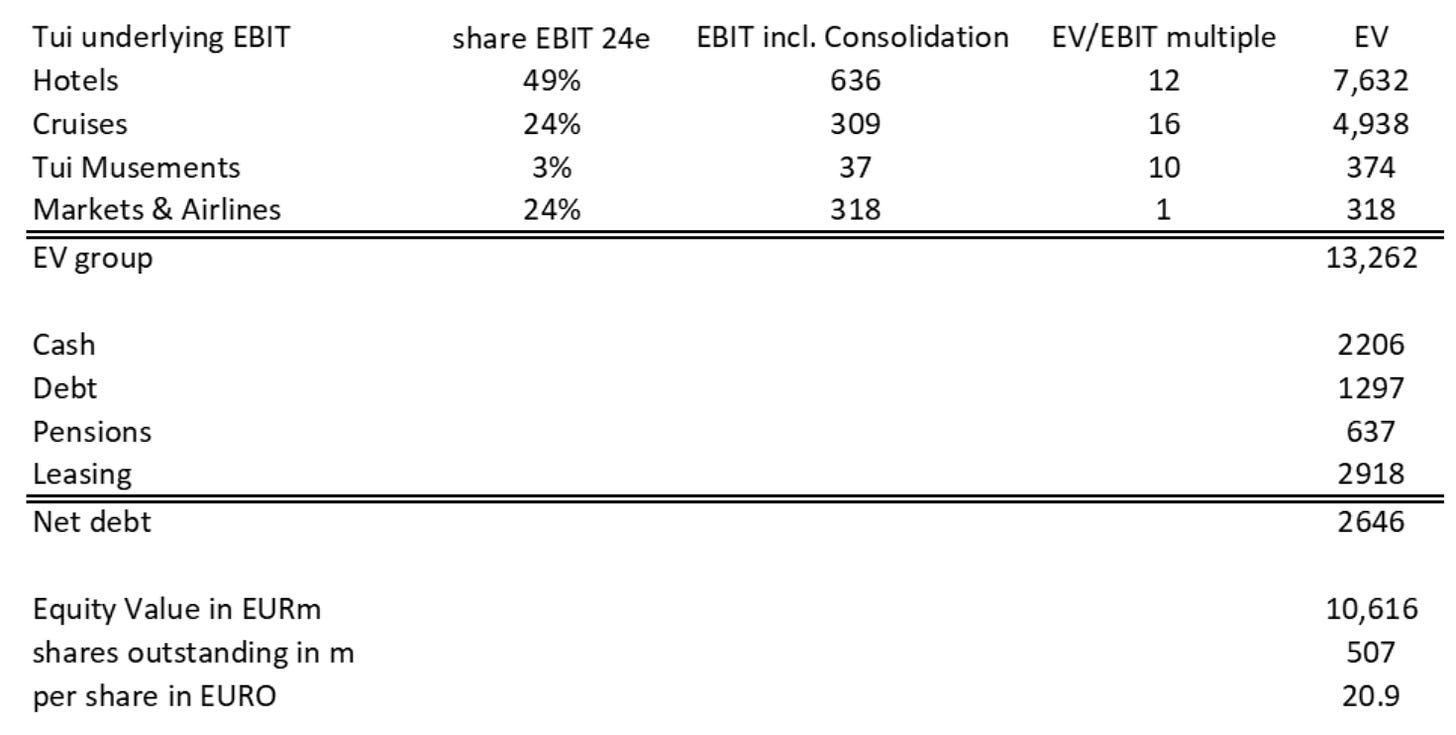

The core thesis of the Value Investors Club analysis is that TUI is misunderstood as a “cyclical, value-destroying tour operator,” when in reality, the majority of its earnings come from its hotel and cruise segments. The tour operator business primarily serves to drive higher occupancy in TUI’s own hotels and cruise ships.

Even if you assign a value of €0 to the tour operator business—which still generates more than €300 million in EBIT annually—and apply market-standard multiples to just the hotel and cruise segments, you arrive at a valuation of roughly €13 billion. After subtracting around €3 billion in net debt, that leaves an equity value of €10 billion.

It sounded too good to be true—and a quick look at the balance sheet showed that TUI appeared to be drowning in debt (a detail the analysis didn’t mention). Still, I wanted to dig deeper.

My First Impression

Edited notes from November 2024, before I invested.

General & Qualitative

Tourism is a highly competitive industry, and TUI has no real competitive advantage.

Growth won’t create value, because it requires additional capital—and the returns on that capital are unlikely to exceed what shareholders could earn elsewhere.

But tourism isn’t going away. People will always want to go on vacation.

The global financial crisis in 2008 had little impact on TUI’s bookings, and after the recent COVID disruption, it took less than three years for booking volumes to return to pre-pandemic levels.

CEO Sebastian Ebel has been with TUI in various roles since 1989, when it was still Preussag AG.

He joined the management board in 2001, left in 2006 due to internal disagreements, returned in 2013, became CFO in 2021, and took over as CEO in 2022. He knows the company inside and out.

TUI is a meaningful player in a durable industry, led by competent management. But it’s not a great business. If I invest, I won’t hold it forever.

Earnings

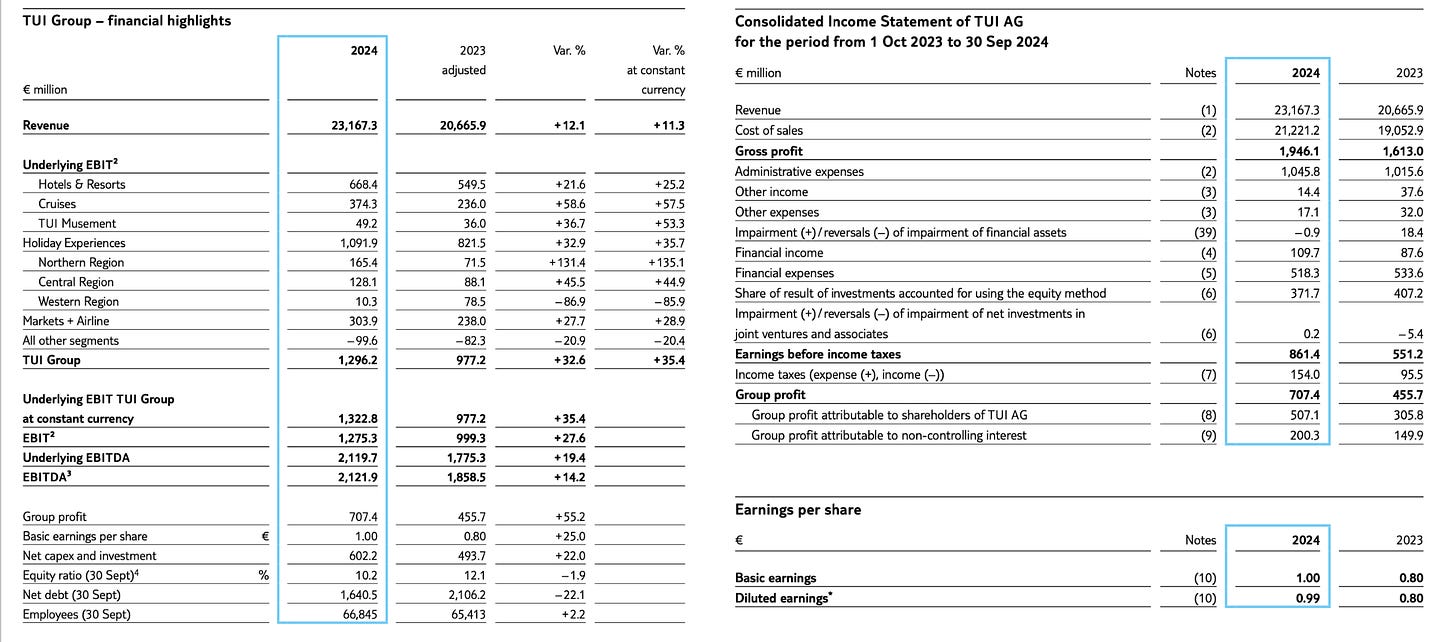

The EBIT figures in the analysis are accurate. They reflect “underlying” EBIT—essentially adjusted EBIT—but the adjustments are minor and not a cause for concern.

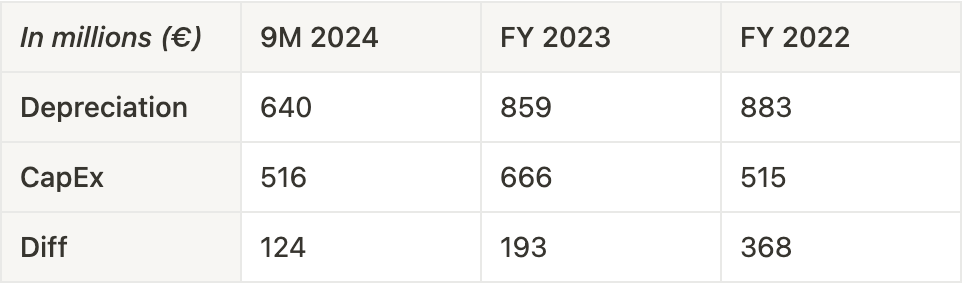

EBIT might actually be understated. TUI’s depreciation expense consistently exceeds its maintenance CapEx, meaning the accounting charge to keep hotels, airplanes, ships, etc. running is higher than the actual cash outflow.

Explanation: If you used the cash expense instead of depreciation to go from EBITDA to EBIT, the EBIT would be significantly higher.

In the best case, this suggests the assets are more durable than the accounting assumes. But it could also indicate that TUI isn’t investing enough to maintain the quality of its asset base.

I don’t know which one is it yet so I’ll just stick to the official EBIT figure.

On the other hand, TUI seems to carry a significant amount of unfunded pension commitments (ungedeckte Pensionszusagen).

In 2024, the loss from the revaluation of pension obligations was €120 million. This doesn’t appear in the P&L, even though it’s an expense that ultimately needs to be funded through TUI’s operating cash flows.

It’s unlikely that such revaluations will result in losses of this size every year, but it’s clearly a material factor.

To stay conservative, I’ll reduce my EBIT estimate by €100 million (more on this in the deep dive section). So instead of the €1.3 billion in EBIT used in the original analysis, I’ll work with €1.2 billion.

At a 10x EBIT multiple, I assume a value of €12 billion less net debt.

A quick discussion on EBIT multiples.

When it comes to EBIT multiples, I prefer to use the same multiple across all investment opportunities. It helps me compare options more objectively. Frankly, I think much of the discussion around sector-specific multiples is overcomplicated. I don’t care that hotel companies are currently trading at 12x EBIT and cruise companies at 16x.

What matters to me is the earnings yield I receive when I buy a business. I aim for a 10% pre-tax return on my capital from day one. That means I won’t pay more than 10x EBIT (after subtracting net debt). And that’s the multiple I apply consistently. (To be fair, I do sometimes pay more—if I believe reported earnings understate true earnings power, or if I think the most recent EBIT figure isn’t representative of normalized profitability. But that’s a separate discussion.)

The core idea is this: using a 10x EBIT multiple gives me a consistent benchmark. It tells me what I’m paying for a 10% earnings yield. That’s what matters—so why would I use different multiples for different companies?

Based on that logic, my initial valuation of TUI was straightforward: €1.2 billion in EBIT × 10 = €12 billion enterprise value, from which I subtract net debt to arrive at the equity value.

Notes continued

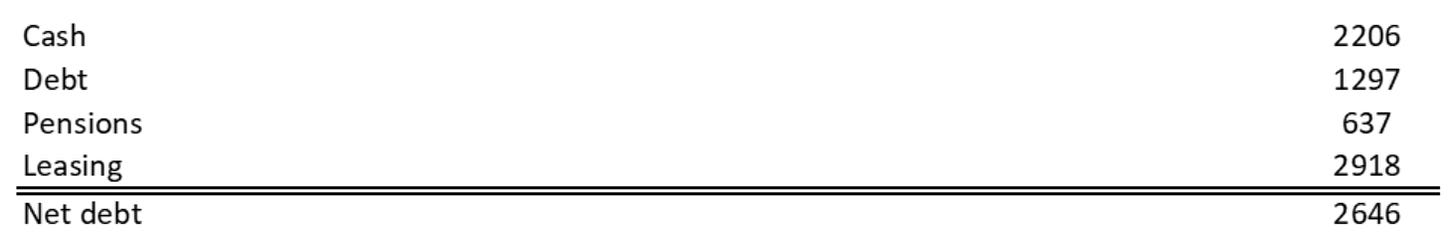

In the original analysis, net debt was calculated as financial debt minus cash, unfunded pension obligations and lease liabilities—resulting in around €2.7 billion.

But €720 million of TUI’s reported cash is restricted, meaning it’s not freely available. So I will exclude that amount and use a net debt figure of roughly €3.4 billion.

That gives me a first estimate of TUI’s equity value based on earnings in the range of €8–9 billion (€12 billion enterprise value minus €3.4 billion in net debt).

Not too bad. But the tricky part will be the balance sheet.

Balance Sheet

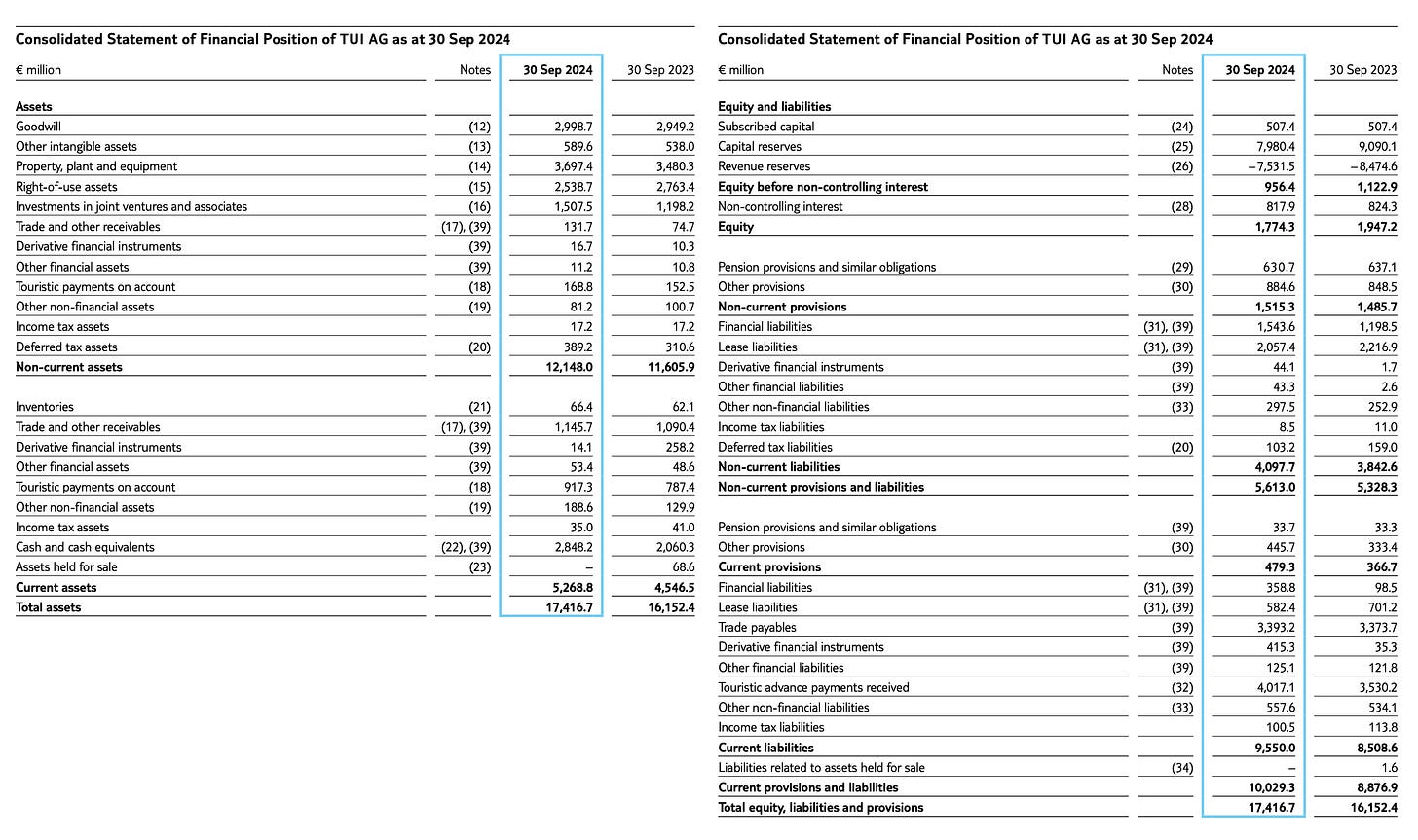

I took a closer look at the balance sheet even during my high-level analysis—but to avoid repeating myself, I’ll go into the details in the deep dive section. So instead of my original notes, this is a summary of my thoughts.

TUIs equity ratio is at just 10%. That’s really dangerous. Under normal circumstances, I wouldn’t even consider investing in a situation like this. But three key points led me to make an exception:

First, this is the balance sheet after three years of COVID. The COVID years were disastrous for TUI, but the company received government support (which it has since repaid in full) and made it through. The balance sheet still reflects a recovery in progress, but the momentum is clearly moving in the right direction. There are also multiple safety mechanisms in place to ensure the company’s survival. While the situation remains risky, I believe it’s reasonable to assume that TUI could even survive another COVID-like shock—however unlikely that may be.

Second, management is open and transparent about the company’s financial position. They acknowledge that the current balance sheet is unsustainable and have made strengthening it a top priority. The progress over the past two years has been impressive.

Third, about €4 billion of TUI’s liabilities are listed as “Touristic advance payments received.” This isn’t debt and doesn’t represent a cash liability. It’s simply an accounting entry showing that TUI has already received customer payments for services it will deliver in the future. It’s effectively free working capital, and it’s likely to grow alongside bookings.

Interim Conclusion

At that point (in November 2024), I felt confident enough in TUI’s undervaluation to invest €30,000—but I also knew I had more work to do.

In-Depth Valuation

It took a lot of work to truly understand TUI. This was by far the most complex analysis I’ve ever done. In the end, I arrived at a valuation that’s significantly lower than my initial estimate—but my conviction in that estimate is much higher. That’s why I felt confident increasing my position from €30,000 to €77,000 as of April 2025.

What made the analysis so challenging were mainly accounting technicalities I initially overlooked (there’s a reason I usually prefer much smaller companies). In addition to the common pitfalls that come up in any solid analysis, TUI had some unique complexities. A few examples:

A significant portion of TUI’s EBIT doesn’t actually belong to TUI—it belongs to minority shareholders. This distinction only shows up below the EBIT line at the net income level, not in EBIT itself.

The pension liabilities are substantial, and if you’re not an expert in pension accounting (I’m not), it takes forever to understand the implications.

To figure out why TUI’s equity declined last year despite reporting a net income of about €700 million (of which €500 million was attributable to TUI shareholders), I had to dig into hedge accounting—which doesn’t show up directly in the P&L but still caused an accounting loss of nearly €600 million.

Borrowing a concept from insurance accounting called “float” helped me realize that €4 billion of TUI’s liabilities actually behave more like equity, which significantly improved my view of the asset side.

Understanding acquisition accounting and goodwill led me to uncover over €5 billion in hidden asset value.

I also discovered that TUI has authorized capital (genehmigtes Kapital) equal to almost 50% of currently outstanding shares, meaning there’s potential for significant future dilution.

I’ll do my best to explain all of these concepts in the valuation deep dive. I’ve learned a lot through this process, and I hope you will too—or at the very least, come away feeling more confident if you’re considering an investment in TUI.

Let’s start with the earnings.

The deep dive, including all accounting explanations and my final valuation, is available exclusively to paid subscribers.

Earnings Power Value (EPV)

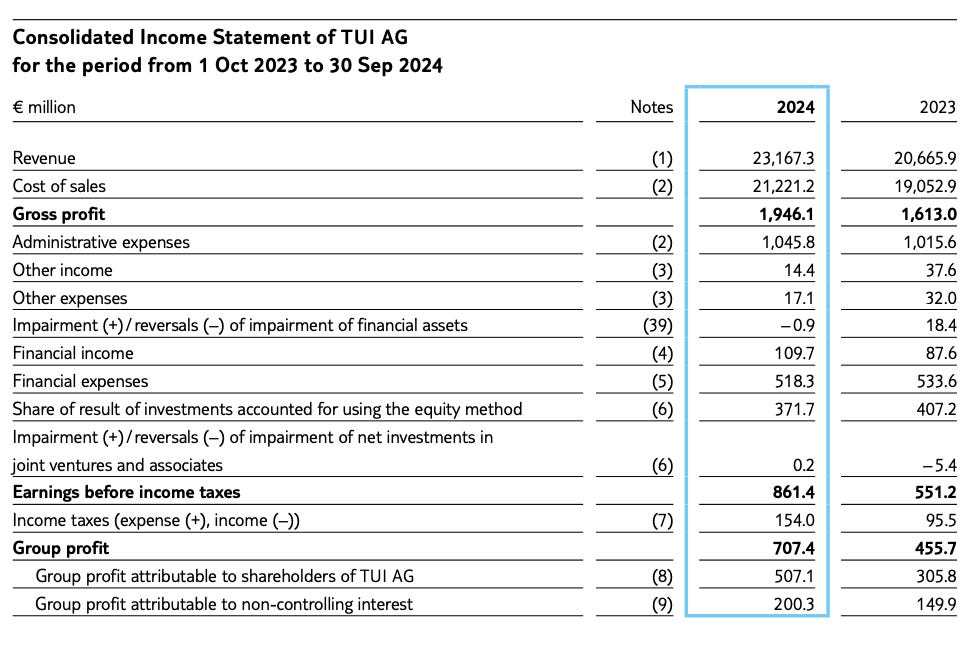

Take a look at TUI’s income statement:

Right at the bottom, under “Group profit,” you can see that €200 million of the €700 million total profit doesn’t belong to TUI, but to other shareholders. This only shows up at the net income level—it’s not reflected in TUI’s reported EBIT.

The Value Investors Club analysis assumes that TUI’s EBIT is already after consolidation and therefore fully attributable to TUI. I think that’s only partly true, and I’ll explain why in a minute. But first, let’s figure out a more conservative EBIT estimate.

In my view, the safer approach is to start with net income attributable to TUI shareholders, which is €500 million. Then we add back:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Till's Value Portfolio to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.