Special Situations Investing

How Buffett Would Make 50% a Year on $1 Million Today - A "You Can Be A Stock Market Genius" Review

(At 50% per year, $1 million would turn into almost $60 million within 10 years.)

“If I was running $1 million today, or $10 million for that matter, I’d be fully invested. Anyone who says that size does not hurt investment performance is selling. The highest rates of return I’ve ever achieved were in the 1950s. I killed the Dow. You ought to see the numbers. But I was investing peanuts then. It’s a huge structural advantage not to have a lot of money. I think I could make you 50% a year on $1 million. No, I know I could. I guarantee that.”

- Warren Buffett

My goal with Till’s Value Portfolio is to stay as close as possible to what I believe Buffett would do today—and let the results fall where they may. I don’t care if there are faster ways to make money. If I don’t think Buffett would do it, I won’t do it.

The challenge with this strategy is that there isn’t just one Buffett to follow—there are at least three. His early investments in the 1950s—the ones referenced in the quote—were very different from the ones that made him famous later with Berkshire, like Coca Cola. And I think the ones he would make today, if he started over with $1 million dollars, would be different from both. Otherwise, he couldn’t guarantee a 50% annual return.

I’m convinced that if Buffett were starting today, he’d focus on extremely small companies and special situations—like mergers, spinoffs, and liquidations. He’d use leverage, and in rare cases, probably even options.

That is not a crazy assumption, given that he used both in the past. The Buffett Partnership used up to 25% leverage. Munger bought Alibaba on margin as recently as 2021 for the Daily Journal portfolio. And both have used options in meaningful ways—most notably, Buffett sold puts on Coca-Cola in 1993 and on the S&P 500 in 2008 (thanks to my friend Henrik for pointing that out).

Buffett used leverage to invest in special situations, mostly merger arbitrage deals. And they were very relevant to his overall performance.

In professors Gerald Martin and John Puthenpurackal’s study of Berkshire Hathaway’s stock portfolio’s performance from 1980 to 2003, they discovered that the portfolio’s 261 investments had an average annualized rate of return of 39.3%. Even more amazing was that out of those 261 investments, 59 of them were identified as arbitrage deals. And those 59 arbitrage deals produced an average annualized rate of return of 81.28%!

[…] If we cut out Warren’s 59 arbitrage investments for that period, we would find that the average annualized return for Berkshire’s stock portfolio drops from 39.38% to 26.96%

- “Warren Buffett and the Art of Stock Arbitrage”, Mary Buffett & David Clark

In later years, Buffett and Munger portrayed themselves as more conservative and long-term oriented than they actually were with many of their investments throughout their careers. Probably because they didn’t want less experienced investors to take on too much risk and lose money. But let’s be clear: you can’t guarantee 50% a year by buying Coca-Cola at a fair price and holding it forever.

I have to admit, it took me a long time to see through that—and I didn’t start studying special situations until recently. Luckily, catching up wasn’t hard—thanks to Joel Greenblatt.

Joel Greenblatt - The Warren Buffett of Special Situations

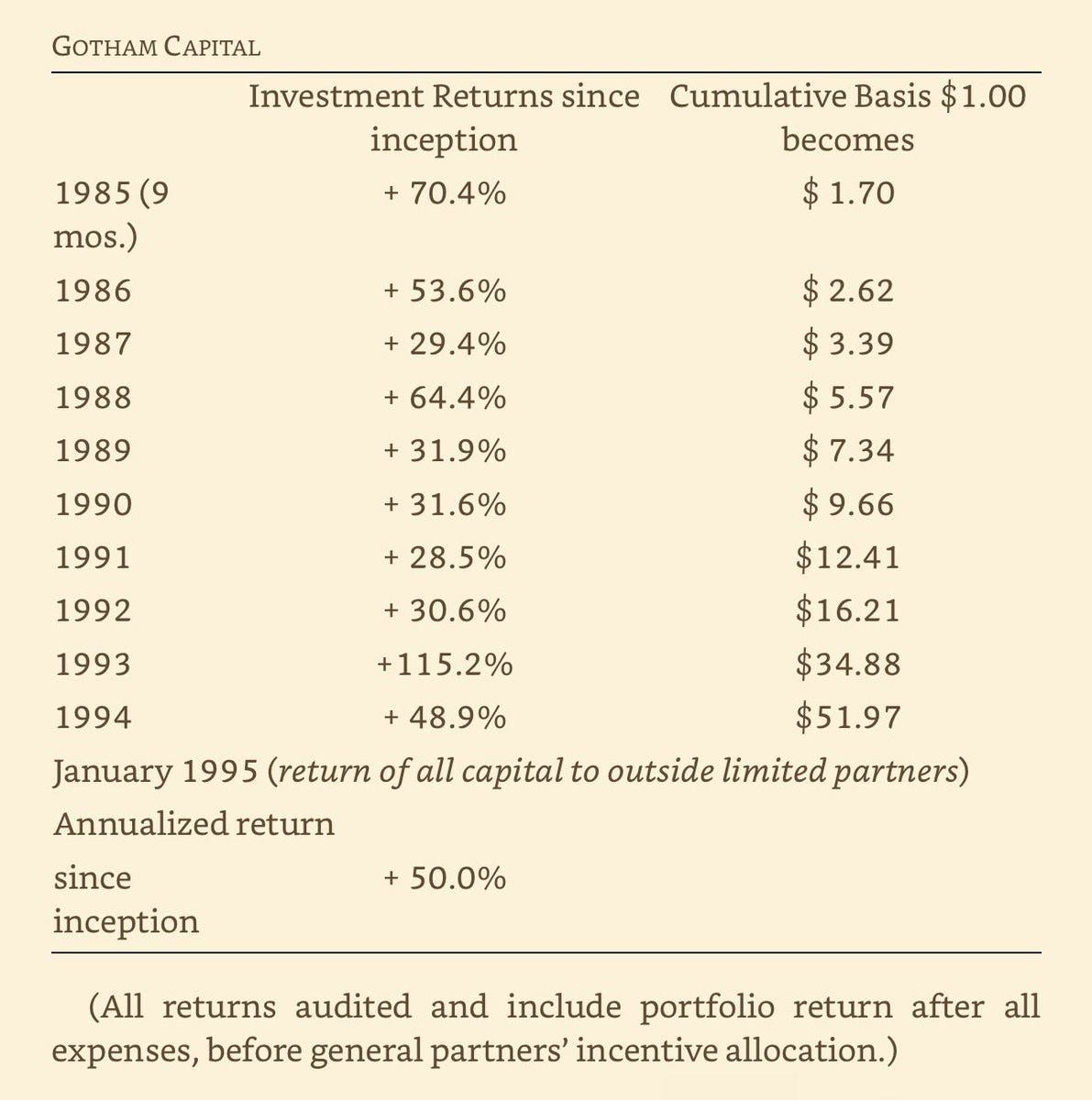

Joel Greenblatt is a fund manager who applied Buffett’s value investing principles specifically to special situations. He launched his fund in 1985 with $7 million and ran it for nine years before returning all external capital. His annualized return was… exactly 50%. In just nine years, $1 turned into nearly $52. That’s an extraordinary track record for any investor—but even more so for a value investor who puts downside protection first.

He wrote a book on value investing in special situations with the unfortunate title You Can Be a Stock Market Genius. The book is a lot better than its title. I can’t remember the last time I learned so much from a single investing book.

My key takeaway is this: I should stick with my approach—value investing with a focus on downside protection—but apply it to areas most investors avoid: tiny companies and complex situations like mergers and spinoffs. And if the risk is extremely low, I shouldn’t shy away from using a small amount of leverage—up to 25% of the portfolio.

So here’s how it works.

These are advanced concepts, and if you’re just starting out, they might be a bit tough to grasp at first. I highly recommend reading the book—it explains everything more clearly and includes lots of valuable case studies.

But if this feels like too much for now, feel free to skip to the end of this post. That’s where I explain how I plan to adapt my investment approach to include special situations—and where I share the three spinoffs currently on my watchlist.

General Advice

When money managers learn valuation and focus on small caps and special situations, they make a lot of money—and then graduate from these opportunities. For someone starting out, there’s always a chance to do original work. There’s turnover in the ranks.

Not all obscure or hidden investment opportunities are attractive. Focus on risk vs. reward and “pick your spots”—only invest in situations you fully understand.

Focus on downside protection first and maintain a healthy margin of safety. In special situations, if you manage the downside well, the upside tends to take care of itself.

Rely on primary sources like SEC filings. There’s no substitute for doing your own homework.

Trade the bad, invest in the good. Hold on to extraordinary companies even if they are fully priced. Sell the others when they reach your intrinsic value estimate.

Spinoffs

Spinoffs are Greenblatt’s favorite type of special situation.

In a spinoff, a public company separates a division into a new, independent business. Shareholders of the parent typically receive shares of the spinoff pro rata—own 1% of the parent, get 1% of the spinoff.

This is, as Greenblatt puts it, “a fundamentally inefficient method of distributing stock to the wrong people.” The parent’s shareholders often don’t care about the spinoff and sell immediately.

That’s also because spinoffs are often just 10%-20% of the parent company, which is too small for many institutional investors. And if the parent is in a major index, like the S&P 500, the spinoff might not be—which leads to more selling.

Studies show that spinoffs tend to significantly outperform the market—especially in the second year after the spinoff. That gives you plenty of time to analyze before buying.

Spinoffs are sometimes used to offload “waste”—debt-laden or underperforming divisions. In those cases, the opportunity is often in the so-called waste, not the cleaned-up parent.

The single most important factor: insider participation. Look for management incentives tied to the spinoff’s future performance, and for insiders retaining or increasing their ownership.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Till's Value Portfolio to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.